Welcome to Part 2 of this series exploring the effect back supports can have on sitting posture. First, to recap:

The back support height and width selection is dependent on a number of factors. The base of the back support generally runs from the height of the posterior superior iliac spines (PSIS) to the chosen height against the user’s back depending on the support needed for stability and the freedom of movement required at the shoulders (e.g. if a wheelchair user is self-propelling).

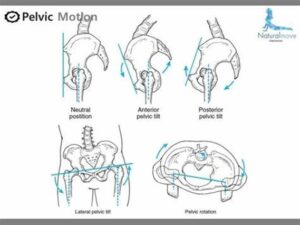

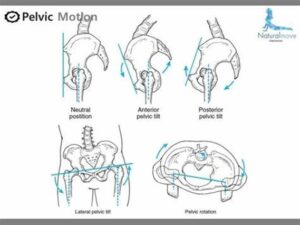

The cushion and back supports are primary surfaces involved in functional seating and both have a direct effect on sitting posture. This is a two-part blog that explores how the back support can offer biomechanical support to maintain pelvic alignment and stability, particularly in the transverse plane (pelvic rotation) and sagittal planes (posterior/anterior pelvic tilt).

We reviewed how the back support can respond to pelvic rotation in Part 1, now let’s explore the following question:

Neutral Alignment

Anterior Pelvic Tilt

Posterior Pelvic Tilt

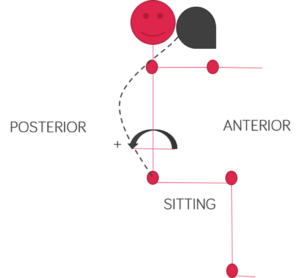

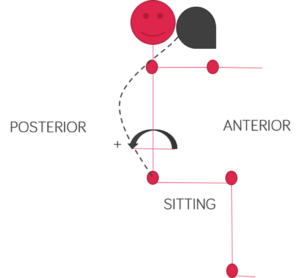

In a neutral pelvic alignment (Figure 1 – top right) we maintain the natural curves of the spine in the lumbar, thoracic and cervical regions. The anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) and posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS) are level, allowing an efficient pelvic position above which the spinal curves are maintained. We tend to move towards slight posterior pelvic tilt in sitting and this can change the alignment of the spinal curves.

(ASIS) and posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS) are level, allowing an efficient pelvic position above which the spinal curves are maintained. We tend to move towards slight posterior pelvic tilt in sitting and this can change the alignment of the spinal curves.

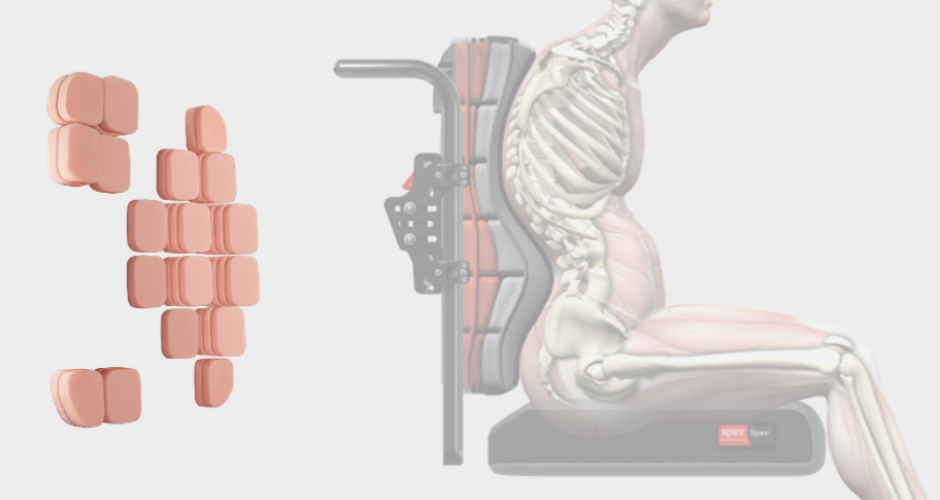

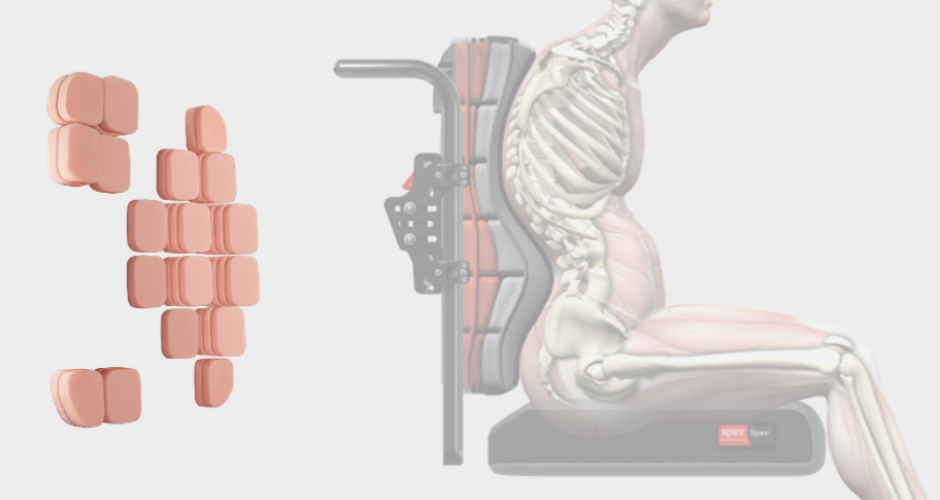

A completely non-contoured (flat) back support will offer support but is unlikely to contour to an individual’s body shape; limited contouring increases the risk of increased pressure to some areas and no support to other areas of the users back and spine. If the back support is soft and pliable this may not be as apparent or severe as it will allow some immersion and envelopment for increased stability and comfort. When there is pelvic asymmetry the spinal curves can become flattened or exaggerated and a flat back support is not able to optimally support, stabilise and distribute pressure over the user’s back unless contouring can be adapted to meet the user’s unique body shape.

Figure 1 Illustration of pelvic in neutral and with asymmetry (http://blog.naver.com/naturalmove/220534758029)

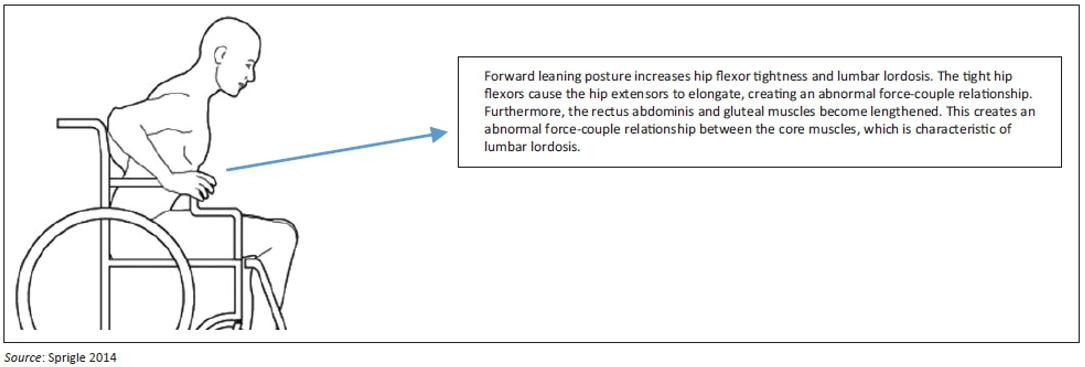

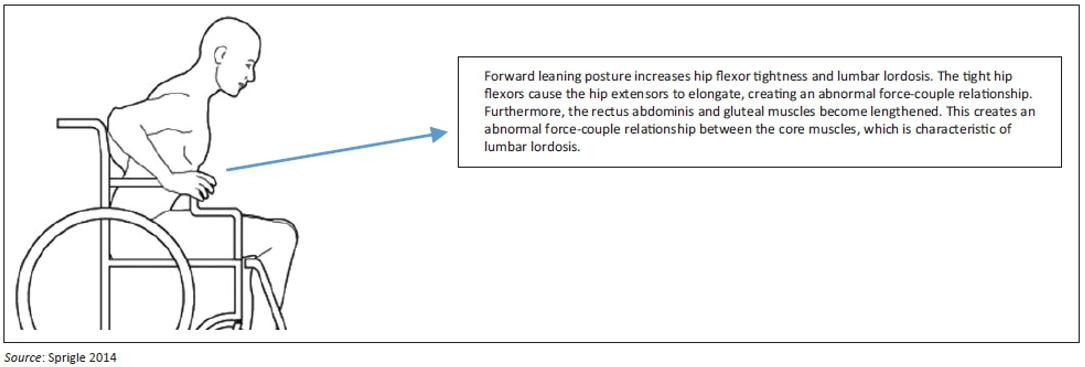

In anterior pelvic tilt the anterior superior iliac spines (ASIS) of the pelvis are lower than the posterior superior iliac spines (PSIS). This reduces the trunk to thigh angle in sitting. The lumbar curve becomes more pronounced and is likely to pull away from the back support. The chest may move forward and the thoracic and cervical spine may move into greater extension to keep the body held up against gravity – the line of gravity moves forward of the pelvis requiring more effort to keep the head up and looking forwards. This means that the wheelchair user needs to work harder to maintain an upright sitting position, is likely to experience fatigue and pain, and may need to rely on their hands to prop whilst sitting for support.

Figure 2 Sagittal plane analysis identifying poor posture. This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY

In posterior pelvic tilt the PSISs are lower than the ASISs and the pelvis rolls backwards. The lumbar curve becomes more flattened with the thoracic kyphosis curve more pronounced. In order to allow the head to be in a functional position, the pelvis may move forward on the seat to accommodate rounded trunk position against an upright/flat back support. The main area of contact on a flat back support will be over the rounded spine, which can lead to discomfort and pain as this area experiences increased pressure against the back support. The wheelchair user may twist side-ways to off-load this pressure and increase comfort, but this will create further postural asymmetry. The line of gravity is likely to fall behind the pelvis which will increase the effort of sitting and the ability freely move the arms and head and neck. This position can also lead to increase pressure risk injury on the user’s bottom and thighs due to changes in the pelvic angle, shear forces and greater pressure over the coccyx.

more pronounced. In order to allow the head to be in a functional position, the pelvis may move forward on the seat to accommodate rounded trunk position against an upright/flat back support. The main area of contact on a flat back support will be over the rounded spine, which can lead to discomfort and pain as this area experiences increased pressure against the back support. The wheelchair user may twist side-ways to off-load this pressure and increase comfort, but this will create further postural asymmetry. The line of gravity is likely to fall behind the pelvis which will increase the effort of sitting and the ability freely move the arms and head and neck. This position can also lead to increase pressure risk injury on the user’s bottom and thighs due to changes in the pelvic angle, shear forces and greater pressure over the coccyx.

The degree of tilt may be non-reducible, meaning we cannot change the alignment of the pelvis in relation to the trunk and thighs, or reducible, meaning we can correct the pelvis towards a more neutral alignment. Assessing pelvic tilt in supine (lying) allows us to see whether it is non-reducible or reducible.

We ideally want a neutral pelvic alignment for optimum trunk stability and function – it allows the upper body to be ‘stacked’ optimally above the pelvis so that the line of gravity falls within the pelvis; this reduces the effort of sitting and also allows greater freedom of movement in the upper limbs and head and neck. Failure to optimally support pelvic alignment can lead to secondary postural asymmetry and deformity. We can use both the seat cushion and the back support to respond to both presentations – we will focus on the back support in this article.

The back support can be adjusted to meet the user’s body in the presence of asymmetry, such as pelvic rotation or pelvic tilt by increasing / decreasing the contouring padding to provide optimal contact along the back of the user’s pelvis (at the level of the PSIS’s) and along the length of the spine.

Non-reducible anterior pelvic tilt

Reducible anterior pelvic tilt

Non-reducible posterior pelvic tilt

4. Reducible posterior pelvic tilt

In this presentation the lumbar spine moves forward and away from the back support surface, whilst gravity may continue to exert a downward force on the trunk increasing this lordotic curve further and, potentially, causing pain. It is important to optimise stability and contact, this can be achieved by contouring the back support to meet the user’s shape, without excessive lumbar contouring that increases this further.

Padding can be reduced behind the soft tissue of the pelvis and added to meet the lumbar curve and provide support to the trunk above – this can simply provide a shelf to help take the weight of the upper body as gravity presses down, minimising further lumbar compression and increased lordosis. A back support that can stabilise the trunk up to the shoulder level is beneficial. Lateral contouring around the trunk can be useful to maintain the trunk stability.

The cushion and/or wheelchair seat can also be adjusted so that the knees are level or slightly higher than the hips to reduce exaggerating anterior pelvic tilt and the back support angle can be reclined for comfort and support based on your clinical assessment findings. Gravity can now be utilised to help the upper body press into the back support for greater stability.

Figure 3 Example of contouring to meet complex asymmetry in the trunk in addition to pelvic asymmetry

By providing an anterior block to the pelvis at the level of the ASIS with a pelvis postural support device, such as a belt, the pelvis can be encouraged into a more neutral alignment. The back support contouring can then be adjusted by reducing the padding in the lumbar area, contour around the pelvis for comfort without pushing forward at level of the PSIS and be contoured around the trunk for increased stability.

The curve of the thoracic spine is likely to be the load-bearing area of the back. In order to optimise comfort and reduce pressure injuries the back can be contoured to meet the shape of the user, padding can be:

- Reduced behind the kyphotic spine and added above and below this area to allow immersion into the back support foam.

- Added on the sides of the back support cushion to allow for increased envelopment and greater pressure distribution over a greater contact area.

- Contoured to meet and support the pelvis, but not to push the pelvis forward.

Figure 4 (Left, Middle) Example of contouring to support posterior pelvic tilt and thoracic kyphosis (Right) Example of less contouring in back support when cushion is used to address potential causes of posterior tilt and obliquity.

Padding can be added at the level of the PSIS and lumbar area to encourage the pelvis to roll forwards into a more neutral position. The pelvic alignment will affect the curves of the spine and therefore with improved alignment less contouring will need to be removed behind the thoracic spine.

A pelvis that is level from the ASIS to PSIS on the wheelchair cushion helps to maintain the natural curves of the spine in the lumbar, thoracic and cervical regions. When we sit, we tend to move into slight posterior pelvic tilt. For this reason we tend to find our most commonly used seat systems (e.g. car seat, office chairs, some armchairs) include an optional lumbar support to maintain a neutral pelvic tilt and optimal trunk alignment whilst we are seated on them. We need to first consider our seat cushion and then our back support cushion, in order to optimise our sitting position in a wheelchair.

The back support angle might also be slightly reclined to meet the pelvic alignment and help the trunk rest against the back support – this position can support a relatively neutral pelvic tilt, but is likely to require contouring in the lumbar regions.

We all adopt different sitting postures depending on our seating surface and, because our body shapes are unique and comfort on the same seating system can vary, we need to consider a combination of contouring and angle adjustment in the seat and back support in the same way as we will not all find the same office chair comfortable in a single configuration.

Back supports should optimise pressure distribution and stability to the pelvis and trunk. The back support can have a direct effect on sitting posture and our aim is to optimise the contouring to positively influence posture to reduce pain during prolonged sitting periods and encourage optimal alignment to support function for quality of life.

- Babinec, M., Cole, E., Crane, B., Dahling, S., Freney, D., Jungbluth-Jermyn, B., Lange, M. L., Pau-Lee, Y.-Y., Olson, D. N., Pedersen, J., Potter, C., Savage, D., & Shea, M. (2015). The Rehabilitation Engineering and Assistive Technology Society of North America (RESNA) Position on the Application of Wheelchairs, Seating Systems, and Secondary Supports for Positioning Versus Restraint. Assistive Technology, 27(4), 263–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400435.2015.1113802

- Costigan, F. A., & Light, J. (2011). Functional Seating for School-Age Children With Cerebral Palsy: An Evidence-Based Tutorial. Language Speech and Hearing Services in Schools, 42(2), 223. https://doi.org/10.1044/0161-1461(2010/10-0001)

- Czaprowski, D., Stoliński, Ł., Tyrakowski, M., Kozinoga, M., & Kotwicki, T. (2018). Non-structural misalignments of body posture in the sagittal plane. Scoliosis and Spinal Disorders, 13(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13013-018-0151-5

- Kobara, K., Eguchi, A., Watanabe, S., & Shinkoda, K. (2008). The influence of the distance between the backrest of a chair and the position of the pelvis on the maximum pressure on the ischium and estimated shear force. Disability and Rehabilitation. Assistive Technology, 3(5), 285–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/17483100802145332

- O’Sullivan, S. B., Schmitz, T. J., & Fulk, G. (2019). Physical Rehabilitation (7th ed.). F.A. Davis.

- Pope, P. (2007). Severe and Complex Neurological Disability. Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-7506-8825-3.X5001-5

- Samuelsson, K., Bjӧrk, M., Erdugan, A.-M., Hansson, A.-K., & Rustner, B. (2009). The effect of shaped wheelchair cushion and lumbar supports on under-seat pressure, comfort and pelvic rotation. Disability & Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 4(5), 329–336.

- Sprigle, S., Wootten, M., Sawacha, Z., Thielman, G., & Theilman, G. (2003). Relationships among cushion type, backrest height, seated posture, and reach of wheelchair users with spinal cord injury. The Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine, 26(3), 236–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/10790268.2003.11753690

- Ukita, A., Abe, M., Kishigami, H., & Hatta, T. (2020). Influence of back support shape in wheelchairs offering pelvic support on asymmetrical sitting posture and pressure points during reaching tasks in stroke patients. PLOS ONE, 15(4), e0231860. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231860

Disclaimer: This information is provided for professional use only,

and as a general resource for clinicians and suppliers.

It is not intended to be used as, or as a substitute for, professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment.

Clinicians should rely on their own professional medical training when providing medical advice or treatment,

and should consult a range of different information sources before making decisions about the diagnosis or treatment of any person.

Your use or reliance on this information is at your own risk.

(ASIS) and posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS) are level, allowing an efficient pelvic position above which the spinal curves are maintained. We tend to move towards slight posterior pelvic tilt in sitting and this can change the alignment of the spinal curves.

(ASIS) and posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS) are level, allowing an efficient pelvic position above which the spinal curves are maintained. We tend to move towards slight posterior pelvic tilt in sitting and this can change the alignment of the spinal curves.

more pronounced. In order to allow the head to be in a functional position, the pelvis may move forward on the seat to accommodate rounded trunk position against an upright/flat back support. The main area of contact on a flat back support will be over the rounded spine, which can lead to discomfort and pain as this area experiences increased pressure against the back support. The wheelchair user may twist side-ways to off-load this pressure and increase comfort, but this will create further postural asymmetry. The line of gravity is likely to fall behind the pelvis which will increase the effort of sitting and the ability freely move the arms and head and neck. This position can also lead to increase pressure risk injury on the user’s bottom and thighs due to changes in the pelvic angle, shear forces and greater pressure over the coccyx.

more pronounced. In order to allow the head to be in a functional position, the pelvis may move forward on the seat to accommodate rounded trunk position against an upright/flat back support. The main area of contact on a flat back support will be over the rounded spine, which can lead to discomfort and pain as this area experiences increased pressure against the back support. The wheelchair user may twist side-ways to off-load this pressure and increase comfort, but this will create further postural asymmetry. The line of gravity is likely to fall behind the pelvis which will increase the effort of sitting and the ability freely move the arms and head and neck. This position can also lead to increase pressure risk injury on the user’s bottom and thighs due to changes in the pelvic angle, shear forces and greater pressure over the coccyx.